Debunking the recent study that claimed penis size has increased (Part 5 – Results)

The systematic dismantlement and meta-deconstruction of a sensational claim that took the world by storm in 2023, that penis length has increased 24% over 29 years globally.

Introduction

In the previous part, we delved into what I believe to be data errors made in the meta-analysis.

In this part, we explore one more oddity in the paper before finally analyzing the correct data and interpreting the results, according to my understanding.

Odd subgroup analysis

After the authors of the meta-analysis discovered the increase in erect penile length worldwide in the data they used, they performed subgroup analyses to account for potential confounding variables. In one of those analyses, they looked at differences by geographic region, taking the regions to be: Africa, Asia, North America, and Europe.

When I glanced at the graph, I immediately noticed that the subgroup analysis revealed a negative temporal trend in mean erect penile length in North America (in blue) and Africa (in light yellow). The increase in length was only in Europe and Asia, but the authors of the meta-analysis don’t appear to have reported whether the negative trends they observed in North America and Africa reached statistical significance.

When I delved deeper, I discovered that this subgroup analysis appears to be inconsistent. The data from Africa, which come from two Egyptian studies by the same author in 2015, appear to have been taken in the meta-analysis to be three years apart (2015 and 2018). The meta-regression line for the region of Africa appears to have been entirely based on these data.

The choices made when dividing the studies by geographic region don’t seem to have been explained in the paper, even though the question is nontrivial. Was it purely a geographic matter of which country was in which region? Or did the authors take into account the genetic makeup of the populations? As far as I can tell from examining the paper, the answer seems to be a mix of both.

The two Egyptian studies seem to have gone into Africa, even though Egypt is in the Middle East and its population is much closer to that of other Middle Eastern countries than to those of most countries in Africa. The Israeli study appears to have gone into Europe, even though Israel is a country in West Asia. The Turkish study also appears to have gone into Europe, even though Turkey is mostly in Asia as well. In Asia, the authors seem to have grouped Saudi Arabia, India, and East Asian countries. North America and Europe were treated as separate regions, even though the populations share the same Caucasian majorities. These choices don’t appear to have followed a clear consistent logic.

The real meta-analysis

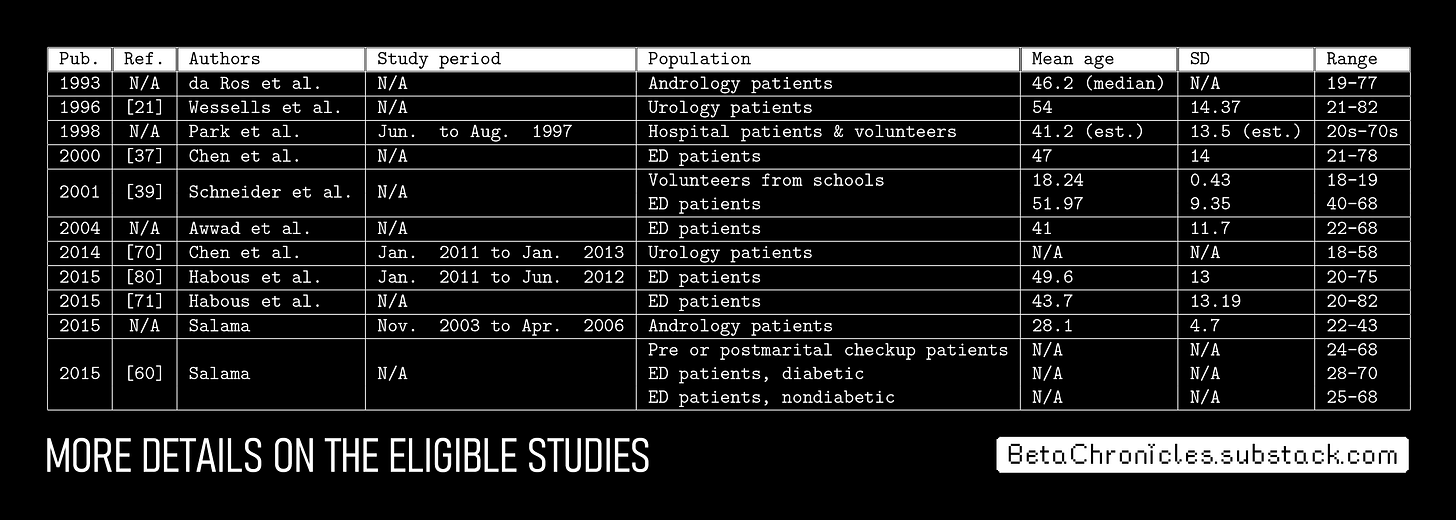

We now arrive at the exciting part of performing the meta-analysis correctly—according to my understanding and interpretation—and investigating whether there really is a global temporal trend in erect penile length. The table below summarizes the studies that are eligible for inclusion in my opinion.

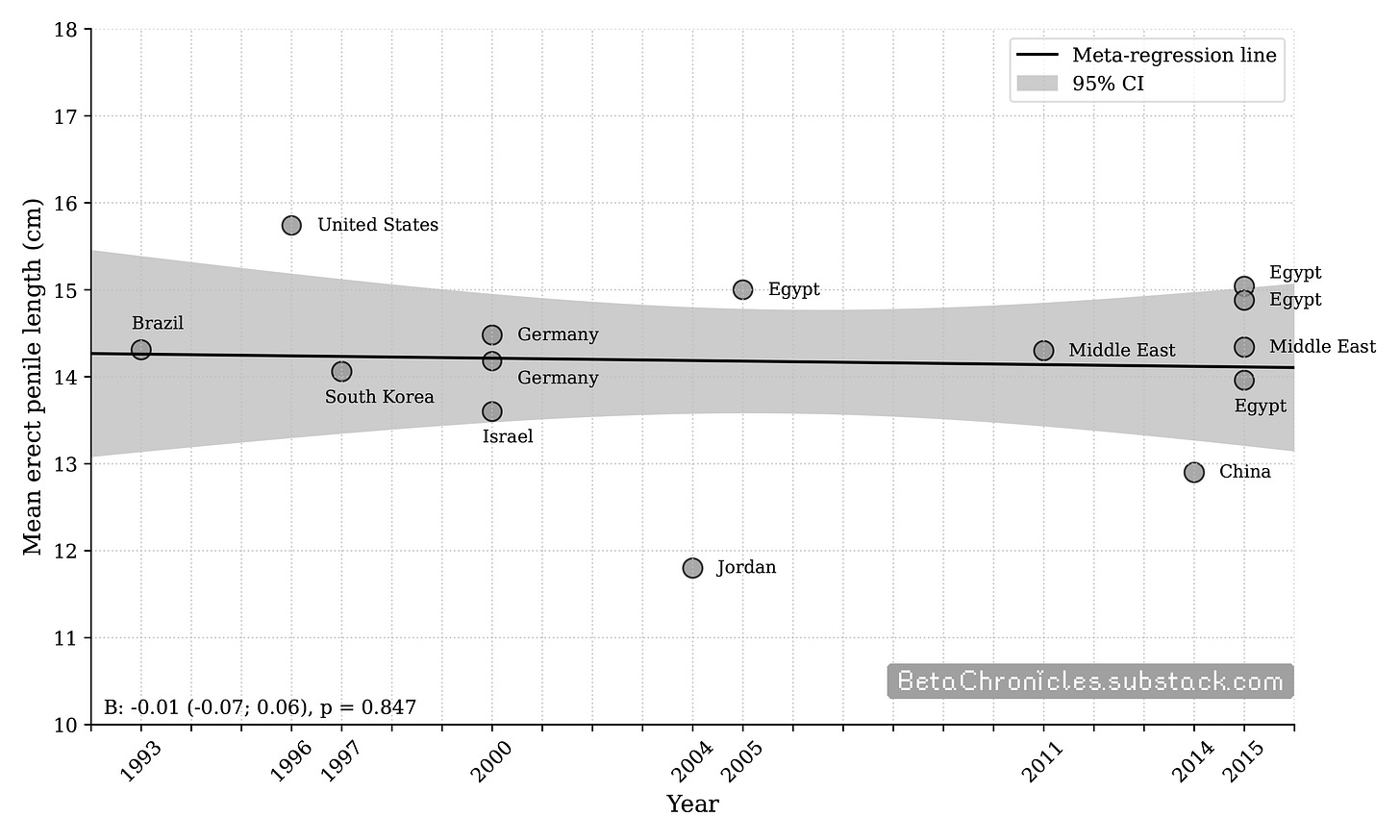

We are left with data spanning 22 years, potentially involving as many as 2,510 men, a mere fraction of the original number. One study is from Latin America (Brazil), one is from the United States, one is from Europe (Germany), two are from East Asia (South Korea and China), and the rest are from the Middle East. There aren’t enough data to perform a meaningful subgroup analysis, so we have to disregard any potential ethnic differences between these studies.

Instead of simply taking each study’s publication year as a variable in the meta-analysis, let’s make a smarter choice and take the average time point of the period during which each study was conducted. This can make a big difference, as in the case of the Egyptian study by Salama on 59 men, where the data were collected from 2003 to 2006 but the study was published in 2015. When the study period isn’t reported, we’ll try to use the submission date of each paper instead of the final publication date for a more accurate picture. The table below summarizes more information about the studies.

The meta-regression with a random effects model reveals a negligible slope in mean erect penile length over the 22-year period (p = 0.847). This means there is a probability of about 85% that the variability throughout the years in these data is completely due to chance and not to a true relationship between the two variables (mean erect penile length vs. year). Thus, the claim that penis length has increased seem unsupported when the meta-analysis is performed correctly, according to my understanding and interpretation.

Postmortem

This exposé debunked the claim that penis length has increased over the past few decades, made in a 2023 peer-reviewed article I believe had numerous methodological issues. The claim of a 24% increase in erect penile length over 29 years was ridiculous to me to begin with. If such a colossal change in one generation were true, I thought to myself, then sons would have a penis 24% longer than their fathers!

The authors speculated that the decline in the age of onset of puberty could have something to do with the supposed increase in erect penile length:

It can be speculated that these changes [in erect penile length] may be linked with observations that pubertal milestones are occurring in younger boys than in the past [92]. Data suggests that earlier pubertal growth may be associated with increased body sizes including longer penile length [93-95].

I found this to be a curious speculation. When I checked the cited studies, I found that refs. [93–95] didn’t seem to support the speculation on penile length, according to my reading at least. Studies [93] and [95] examined the association of obesity with the age of onset of puberty in boys, while study [94] found that early puberty in boys led to smaller gains in height during the growth spurt. None of these three studies appear to “suggest” that earlier pubertal growth may be associated with longer penises.

The more I thought about this speculation, the more odd it seemed. Any study that might potentially support the claim of an association between early puberty and longer penile length would have to make flaccid or stretched measurements on the boys. Since the age of onset of puberty has gone down in recent years, then why didn’t the meta-analysis find a temporal trend in flaccid or stretched length? Why did it find a significant increase in erect penile length only?

The sensational claim of a 24% increase—sometimes rounded up to a nicer 25%—initially went viral and was covered by many news outlets. None seem to have raised any questions about it. Even Dr. Larry Lipshultz, one of the world’s foremost urologists, weighed in with his own speculative hypothesis: that perhaps pornography made men masturbate more, so their penises elongated simply by virtue of having more frequent erections.

You might possibly blame online porn, but that’s just a theory. The more someone has erections, there might be greater potential for better erections. The tissue would stretch more, hence would get longer.1

Much ado about nothing, in my opinion, as this exposé meticulously documents. If you’ve read until here, you might be shocked by the facts surrounding this matter, and you might be left wondering how the possible errors I identified could have gone unnoticed in a peer-reviewed study that received widespread news coverage. I’m just as perplexed as you are.

I should make it clear that I have no reason to believe there was any deliberate wrongdoing by the authors in this matter. I have no reason to doubt that these were probably mistakes made in good faith when reviewing the literature and analyzing the data. I do think, however, that the article should be retracted based on the potential issues I identified.

If I had been in the shoes of the authors, the German study by Schneider et al. in 2001 would have definitely given me some pause vis-à-vis the paper’s finding. That study compared a group of young volunteers (18 to 19 years old) to a group of older patients with erectile dysfunction (40 to 68 years old, with a mean age of 52). That’s a mean age difference of 34 years between the two groups. Schneider et al. found no statistically significant discrepancy in erect penile length (14.48 cm [5.7 in] in the 111 young volunteers vs. 14.18 cm [5.6 in] in the 32 older patients). This would have prompted me to re-examine the scholarly evidence in search for any possible errors.

Conclusion

“Don’t believe everything on the internet,” Dr. Michael Eisenberg posted on X on July 17, 2024, warning against misleading medical information on YouTube. I agree with Michael, but I would amend his warning to add that you shouldn’t believe everything you read in the news about science, either. In fact, in my opinion, you shouldn’t even believe everything you read in the peer-reviewed scientific literature—even systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

I think you should really only believe something if it’s been rigorously proven and consistently replicated, with multiple lines of evidence to support it. Short of that, it’s always a good idea to maintain a healthy degree of skepticism when reading even the scientific literature.

The ball is now in the other court. How will the authors and journal react to these methodological issues? Will the authors address the debacle and issue an explanation, or will they choose to ignore it? Will the journal retract the study, or will it sweep the matter under the rug? What about the media outlets and podcasts that helped propagate the sensational claim? Will they issue corrections to their published articles and write new stories announcing that penis size hasn’t increased after all, or will it be a nonstory?

I hope we will soon have the answers to all these questions.

👍 Leave a like on this post before reading the next part, where I uncover disturbing revelations about the paper.

Rauf, D. (2023, February 14). Penises Have Gotten Surprisingly Longer Over the Past 29 Years, Study Finds. Everyday Health.