Debunking the recent study that claimed penis size has increased (Part 6 – Disturbing revelations)

The systematic dismantlement and meta-deconstruction of a sensational claim that took the world by storm in 2023, that penis length has increased 24% over 29 years globally.

Introduction

In the previous part, we performed the meta-analysis with the correct data, and the results debunked the original claim of a global increase in penile length.

In this part, we uncover some disturbing revelations about the paper.

Disturbing revelations

When I published the fifth—and what I thought would be the final—part of this exposé, I emailed the paper’s lead and supervising authors on April 8, 2025, to notify them of the methodological issues I had identified in their work and ask if they had any comments about it. I also contacted the editor-in-chief of the journal in which the paper was published. As of this writing, on April 18, I haven’t heard back from any of them.

Since then, I made two discoveries that warranted this follow-up. First, I became aware that I wasn’t the first person to speak publicly about the paper’s methodological issues and to notify the authors and journal editor about them. Second, I noticed that parts of the 2023 paper bear a notable resemblance to another paper published in 2014 by different authors. I expound on both discoveries below.

Previous criticism

On August 14, 2024, Randy Robertson, an English professor at a liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, wrote an opinion piece in The Times Higher Education criticizing the lack of accountability for reviewers in the academic peer review process.1

When an academic article is being peer reviewed, the identity of the reviewers almost always remains unknown to the authors and to the public. When reviewers do a bad job, there are no repercussions. The gist of Robertson’s argument was that peer review would be better if reviewers were named and rated. (I personally think the peer review process is a scam that serves to perpetuate a parasitic business model, but that’s a story for another day.)

To illustrate his argument, Robertson examined the paper that claimed to have found the global colossal increase in penile length. He identified some of the same issues I have, most notably the inclusion of studies based on self-measurement, contrary to what was reported in the systematic review’s selection criteria.

Robertson wrote that he corresponded with the paper’s authors and with the journal editor. According to his account, the authors acknowledged the methodological issues and expressed their intent to revise the paper. Based on the timeline he described, this exchange likely occurred some time in late 2023. As of April 2025, however, no correction or revision has been issued.

I sent my concerns to the corresponding author and then to the journal’s editor. The rhetoric of their response was fine: the authors acknowledged the problems and even thanked me for pointing them out, which must have been hard. Nonetheless, though they vowed to revise the article, neither they nor the journal editor has yet published a correction eight months on.

This timelines prompted me to revisit a May 2024 podcast appearance by Michael Eisenberg, the paper’s supervising author.2 On that podcast, he spoke again about the systematic review and meta-analysis. He reaffirmed the claim of a global increase in penile length but he seemingly made no mention of the paper’s methodological issues.

If Robertson’s account in The Times Higher Education is accurate, then Eisenberg was potentially already aware of those issues by the time of his podcast appearance. I emailed Eisenberg again on April 13 for clarification on this matter, but I haven’t heard back as of April 18.

Notable resemblance

My investigation led me to another discovery, more disturbing than any of the methodological issues I identified. Before the publication of the 2023 paper, there was one other systematic review and meta-analysis on penis size in the literature, published in 2014 in BJU International.3 The paper, by Veale et al. from King’s College in London, aimed to establish nomograms for both penile length and circumference based on the available scholarly data, relying on a total of 20 studies.

As this paper was highly relevant to the 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis, I expected it to be cited and discussed in the text. According to Google Scholar, that paper had already been cited more than 200 times in other scholarly work by 2023, but strangely enough, it was seemingly not cited in the 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis.

This made me curious to read the 2014 paper. When I did, I was shocked to find striking similarities with the 2023 article in two places: in the systematic review’s selection criteria for the literature search, and in the tables summarizing the studies that were included.

Selection criteria

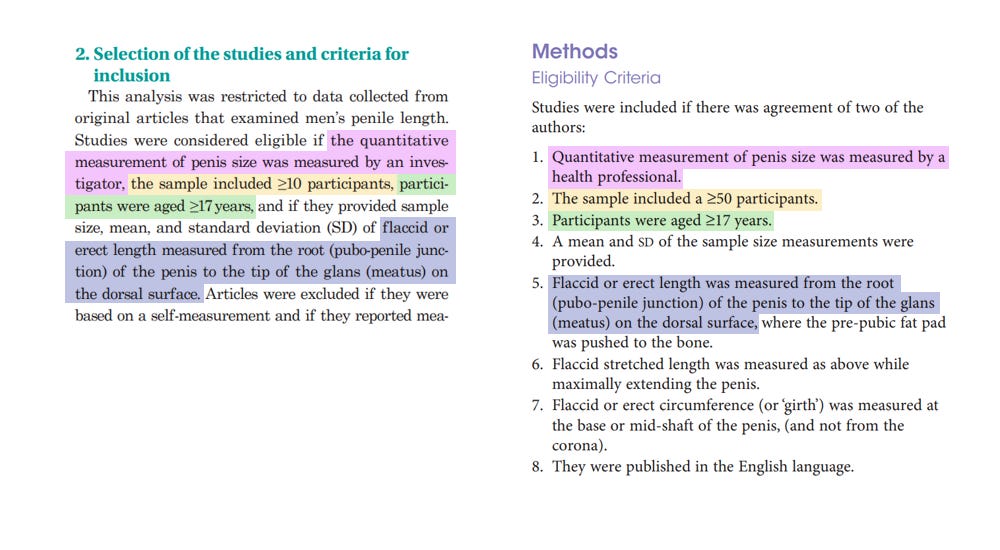

The criteria of both systematic reviews are oddly similar, not only in content but also in form. As shown in the image below, they are given in the same order and use strikingly similar language, even when it’s clunky at times. Notice, for example, the awkward repetition in both papers: “the quantitative measurement… was measured.” The minimum age for participants—17 years old—was the same in both papers, and this criterion was formulated in the same British-sounding language construction: “participants were aged ≥17 years.”

Furthermore, the 2014 paper had separate criteria for the measurement procedure: criterion number 5 dealt with flaccid and erect lengths, while criterion number 6 dealt with stretched length. The 2023 paper, however, only mentioned flaccid and erect length in its measurement criterion, and no mention was made of stretched length at all. The criterion in the 2023 paper is strikingly similar to the one in the 2014 paper, almost a word-for-word resemblance.

Summary tables

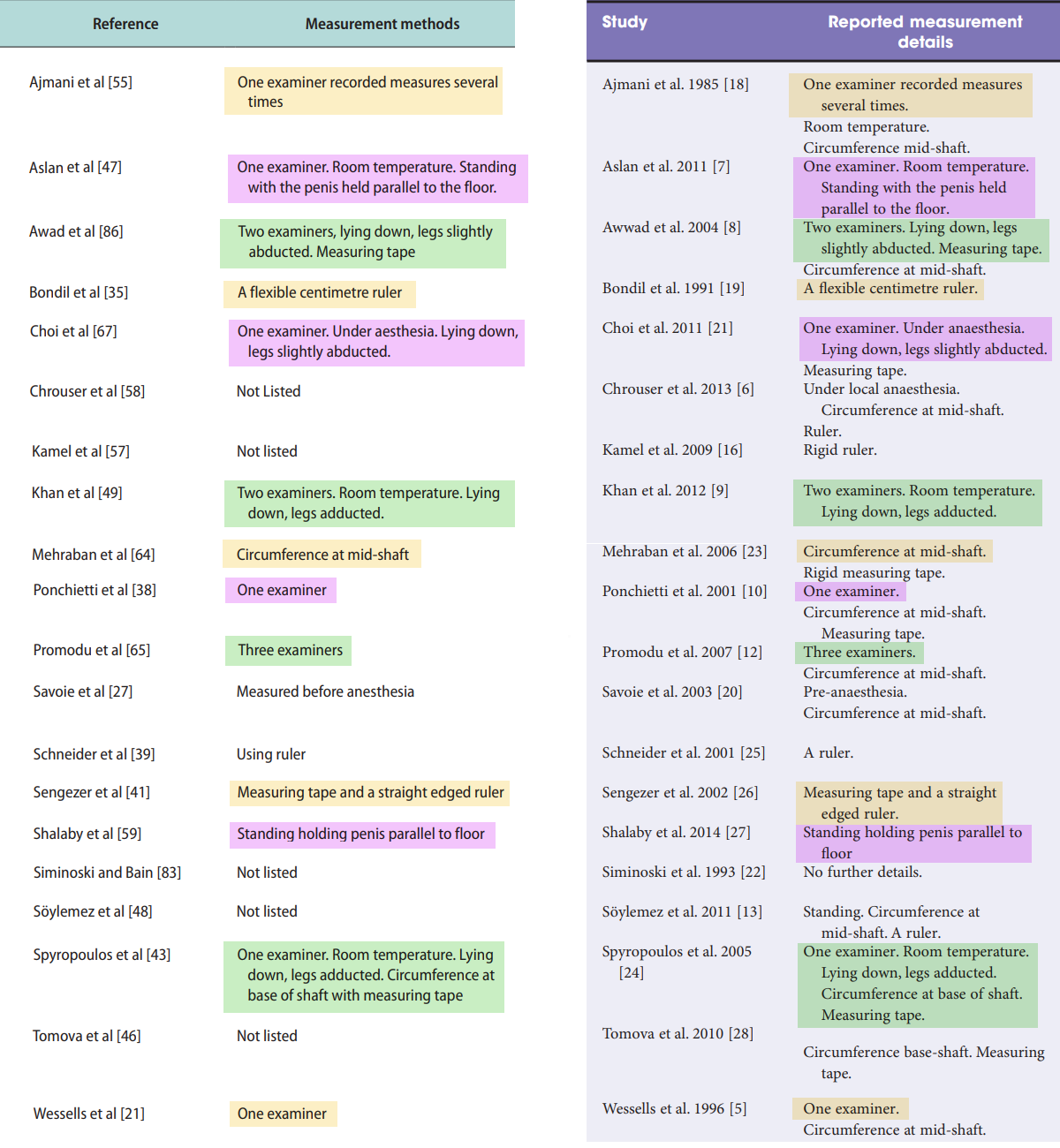

Both papers included a table summarizing information from the studies that met the inclusion criteria. There were 20 studies in the 2014 paper and 75 studies in the 2023 paper. Both tables included a column that contained details on the measurement procedure in every study. In the 2014 paper, this column was titled “Reported measurement details.” In the 2023 paper, it was called “Measurement methods.”

Neither paper explained exactly what information this column contained. In some places, it reported how many examiners carried out the measurements. In other places, it reported the physical position of the participants during measurement. In yet other places, it reported the measuring tools that were used, or how the measurement was performed.

When I examined the tables side-by-side, I found remarkable similarities in this column, as shown in the image below. The 2023 paper included all the 20 studies that the 2014 paper relied on, and the details on most of those studies appear to be exactly the same in both papers. While this isn’t surprising in cases where the details were brief—e.g., “One examiner”—the similarity is striking in the more complex cases, down to the punctuation: e.g., “One examiner. Room temperature. Lying down, legs adducted.”

But even in the simple cases, some errors and linguistic idiosyncrasies appear to be the same. For instance, the details on the Turkish study by Şengezer et al. in 2002 are reported in both papers as “Measuring tape and a straight edged [sic] ruler,” where the compound adjective should obviously have been hyphenated. Curiously enough, the text of the Turkish study correctly hyphenates “straight-edged,” so how did the error in the 2023 paper originate?

The similarities also extend to the use of British spelling. In the case of the French study by Bondil et al. in 1991, the measurement details in the 2014 paper were reported as “A flexible centimetre ruler.” The spelling of “centimetre” follows the British form, as the authors are from the U.K. Curiously enough, the 2023 paper—mainly by Stanford researchers in California—also used the British spelling. What is more surprising is that the original study by Bondil et al. in 1991 used the American form: “centimeter.” So, where did the British spelling in the 2023 paper come from?

The oddities don’t stop there. The 2014 paper examined penis size in both dimensions: length and circumference. Therefore, it included details on the experimental procedures for both length and circumference measurements. The 2023 paper, however, was a systematic review and meta-analysis solely on penile length. It’s very odd, then, that it also included details on the circumference measurements—details which are strikingly similar to the ones in the 2014 paper.

For instance, the measurement details in the study by Mehraban et al. in 2006 were simply reported as “Circumference at mid-shaft” in both papers, even though that study included much more detail on its methods for penile length measurement. The summary table also included details on circumference measurements in the 2005 study by Spyropolous et al.

Beyond the similarities in content and form between the two works, the 2014 paper might elucidate the mystery behind the unexplained omission of certain data from the 2023 systematic review. If you remember, my investigation led me to find that data were omitted from the German study by Schneider et al. in 2001 and from the Jordanian study by Awwad et al. in 2004.

The German study measured flaccid and erect length in two groups: young volunteers, and older patients with erectile dysfunction. The Jordanian study also included two groups: men with erectile dysfunction, and controls. Flaccid and stretched length were measured in both groups in the Jordanian study, but erect length was only measured in the group with erectile dysfunction.

The 2014 paper, in its systematic review’s selection criteria, excluded data on erectile dysfunction patients. It therefore included only the group of young volunteers from the German study, and the group of controls from the Jordanian study. The 2023 paper, however, didn’t exclude erectile dysfunction patients. Nevertheless, it also omitted the data on the erectile dysfunction group in the German study, and it reported only flaccid and stretched measurements from the Jordanian study (remember that in this case, erect length was only measured in the erectile dysfunction group).

On April 13, 2025, I emailed both the lead and supervising authors of the 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis. I asked if they had relied, in any way, on the 2014 paper by Veale et al.—a paper they seemingly didn’t cite in their manuscript. As of April 18, I haven’t heard back from either of them.

Summary

In addition to the methodological issues I identified in the previous parts of this exposé, we add two new discoveries to the perplexing mix.

First, the authors seem to have been made aware of some of the issues as early as 2023—according to Randy Robertson—and they reportedly promised to issue a correction that, more than a year later, still hasn’t appeared.

Second, there are striking similarities between the 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis, and its only predecessor in 2014 by Veale et al. I don’t want to make an accusation of plagiarism—especially since I don’t know the perspective of the authors on this matter. But if these similarities are purely accidental, resulting from independent reading of the original sources, it would indeed be a truly extraordinary coincidence. My requests for comment and clarification on this matter have, unfortunately, gone unanswered.

These two new discoveries add to the murky pile and make it even more urgent for the authors to address this matter publicly and for the journal editor to re-evaluate the paper’s publication in light of this exposé. I offered the authors to publish any comments they might have on this matter, at any time of their liking, and that offer still stands.

I also contacted multiple media outlets that originally covered the sensational claim of a global increase in penis size. Only one wrote back to me, promising to issue an article correction but only in the event the paper is retracted. I’m afraid that is the only good news to report in this whole story. Given the seriousness of the issues highlighted so far, I personally believe that retraction is only a matter of time. The real question is how long it will be before that happens.

Robertson, R. (2024, August 14). Peer review will only do its job if referees are named and rated. The Times Higher Education.

The Diary of a CEO. (2024, May 9). The Male Fertility Doctor: Delaying Having Kids Is Impacting Your Future Kids! Dr Michael Eisenberg [Video]. YouTube.

Veale, D., et al. (2014). Am I normal? A systematic review and construction of nomograms for flaccid and erect penis length and circumference in up to 15 521 men. BJU International, 115(6), 978–986.